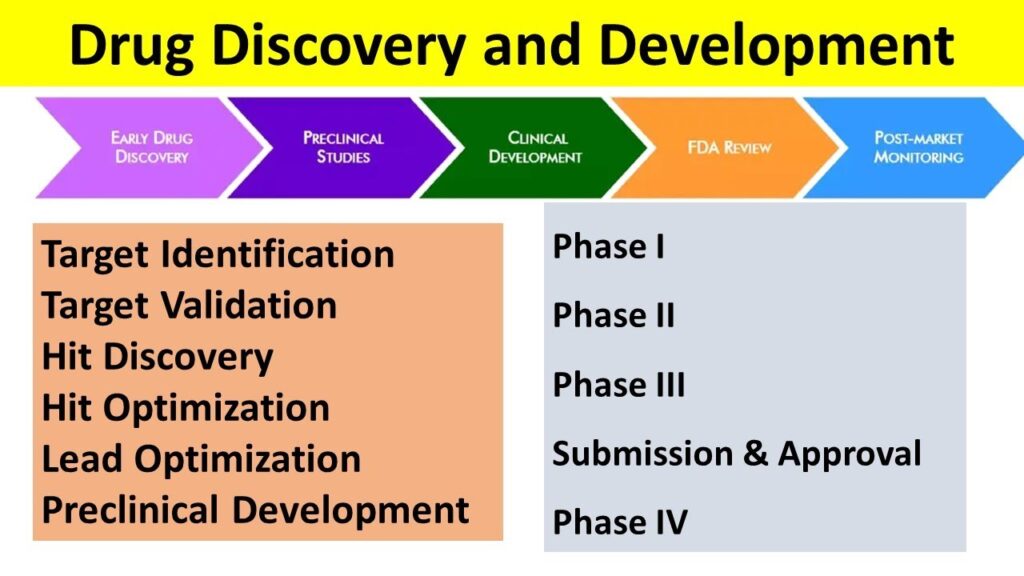

In a traditional manner, drug discovery is a very complex, multi-stage, and costly process aimed at identifying new therapeutic compounds that can treat specific diseases. Typical drug discovery takes several years, involving various scientific disciplines like biology, chemistry, pharmacology, and toxicology [1, 2]. Here’s a general overview of the process, from initial target identification to clinical development [3-6]:

Stage 1: Target Identification and Validation

- Objective: The first step is identifying a biological target (usually a protein, enzyme, receptor, or gene) that is involved in the disease process. The goal is to find a target whose modulation (activation or inhibition) can have a therapeutic effect.

- Methods:

- Genomics: Identifying genes linked to disease susceptibility or progression.

- Proteomics: Analyzing protein interactions, expressions, and post-translational modifications.

- Literature Review: Studying existing research to identify well-characterized drug targets.

- High-Throughput Screening (HTS): Screening large libraries of compounds to identify those that interact with the target.

- Validation: After identifying a potential target, it must be validated by demonstrating that modulating the target has a measurable effect on disease pathways. This may involve knocking out or overexpressing the gene in animal models or cell cultures.

Stage 2: Hit Discovery and Optimization

- Objective: Once a target is validated, the next step is to identify “hits”—compounds that interact with the target and have some biological activity.

- Methods:

- High-Throughput Screening (HTS): Large compound libraries are screened against the target to identify “hits” that bind and elicit a biological response.

- Virtual Screening: Computational methods to predict how small molecules might interact with the target based on their 3D structure.

- Fragment-Based Drug Discovery: Screening smaller fragments of molecules and optimizing them to create a potent drug.

- Outcome: Hits are initially identified based on their ability to bind to the target or modulate its activity in a desirable way.

Stage 3: Lead Optimization

- Objective: Hits identified in the previous step are further optimized to improve their potency, selectivity, and drug-like properties (e.g., stability, solubility, and bioavailability).

- Methods:

- Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR) Studies: Synthesizing analogs of the hit compounds to determine which chemical modifications enhance activity or reduce toxicity.

- Computational Drug Design: Using molecular docking, molecular dynamics simulations, and other computational methods to predict how changes to the compound’s structure will affect its interaction with the target.

- In vitro assays: Testing the lead compounds for potency, selectivity, and other biological parameters.

- Outcome: The goal is to identify a lead compound with strong efficacy, minimal off-target effects, and suitable pharmacokinetic properties.

Drug Discovery steps

(Source: YouTube)

Stage 4: Preclinical Development and Testing

- Objective: Before a drug candidate can enter clinical trials, it must undergo extensive preclinical testing to evaluate its safety and efficacy in animal models.

- Key Aspects:

- Toxicity Studies: Assessing acute and chronic toxicity, organ-specific toxicity, mutagenicity, and carcinogenicity in animal models.

- Pharmacokinetics (PK): Studying the absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) properties of the compound.

- Pharmacodynamics (PD): Understanding how the drug interacts with the body, including its mechanism of action, dosing regimen, and duration of action.

- Efficacy Studies: Testing the drug in disease models to demonstrate its therapeutic potential.

- Outcome: Preclinical testing provides essential data to ensure that the compound is safe enough for human trials.

Stage 5: Clinical Trials (Phase I, II, and III)

- Objective: Clinical trials test the drug’s safety, efficacy, and optimal dosing in humans. This phase is regulated by government agencies (e.g., the FDA in the U.S.).

- Phase I:

- Focus: Safety, dosage, and pharmacokinetics.

- Participants: A small group (20–100 healthy volunteers or patients).

- Goal: Determine the safety profile, maximum tolerated dose (MTD), and initial pharmacokinetic properties.

- Outcome: Phase I trials assess the drug’s safety in humans and identify side effects.

- Phase II:

- Focus: Efficacy and side effects.

- Participants: A larger group of patients (100–500) with the disease the drug is intended to treat.

- Goal: Test efficacy, optimal dose, and further safety data.

- Outcome: Phase II trials provide the first evidence of whether the drug works in humans for the intended indication.

- Phase III:

- Focus: Confirmation of efficacy, monitoring of adverse reactions in larger populations.

- Participants: A large, diverse group of patients (1000–5000).

- Goal: Confirm effectiveness, monitor long-term side effects, and compare the drug to existing treatments.

- Outcome: Successful Phase III trials provide robust evidence of efficacy and safety, leading to regulatory submission.

Stage 6: Regulatory Review and Approval

- Objective: Once the clinical trials are completed, the drug is submitted for regulatory approval. This involves compiling all the data from preclinical and clinical testing to demonstrate that the drug is safe, effective, and meets the required standards.

- Process:

- New Drug Application (NDA): The drug developer submits an NDA to the regulatory agency (e.g., the FDA, EMA) with all data from clinical trials.

- Review: The regulatory agency evaluates the data, conducts additional analyses, and may request more information or studies.

- Approval: If the agency is satisfied with the data, the drug is approved for marketing. If the drug is approved, it can be sold to the public.

- Outcome: The drug is granted marketing authorization, and the company can begin distribution.

Stage 7: Post-Marketing (Phase IV) and Surveillance

- Objective: After the drug is approved and marketed, ongoing monitoring is essential to ensure continued safety and efficacy.

- Key Aspects:

- Pharmacovigilance: Monitoring adverse events and long-term side effects in the general population.

- Real-World Evidence (RWE): Collecting data from patients outside of controlled clinical trial settings to monitor effectiveness and safety.

- Post-Marketing Studies: Conducting additional studies to explore other indications, potential drug interactions, or long-term effects.

- Outcome: Any new findings can lead to additional labeling, regulatory actions (e.g., recalls), or approval for additional indications.

References

- [1] Mohs, R. C., & Greig, N. H. (2017). Drug discovery and development: Role of basic biological research. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: Translational Research & Clinical Interventions, 3(4), 651-657.

- [2] Berdigaliyev, N., & Aljofan, M. (2020). An overview of drug discovery and development. Future medicinal chemistry, 12(10), 939-947.

- [3] Link, W., & Link, W. (2019). Drug Discovery and Development. Principles of Cancer Treatment and Anticancer Drug Development, 87-136.

- [4] Chawla, G., & Pradhan, T. (2024). 2 Lead-hit-based methods for drug design and ligand identification. Computational Drug Discovery: Molecular Simulation for Medicinal Chemistry, 23.

- [5] Sinha, S., & Vohora, D. (2018). Drug discovery and development: An overview. Pharmaceutical medicine and translational clinical research, 19-32.

- [6] Mittal, P., Chopra, H., Kaur, K. P., & Gautam, R. K. (2023). New drug discovery pipeline. In Computational Approaches in Drug Discovery, Development and Systems Pharmacology (pp. 197-222). Academic Press.

This content was generated via Generative AI and enriched, edited by a human.

Be First to Comment